In an era before wellness became a lifestyle hashtag, before cryotherapy chambers and silent retreats became trendy, America had its own booming spa movement — one rooted not in minimalism, but in opulence. The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw the rise of grand spa resorts across the United States, where health, leisure, and social hierarchy collided in fascinating ways.

Today, as we continue to navigate what wellness means — and who it’s for — it’s worth revisiting these iconic healing destinations. Because beneath their gilded domes and mineral waters lie stories that still shape the way we “do” wellness today.

When health was a social affair

Turn-of-the-century spas weren’t just places for healing the body. They were destinations for performing identity, status, and refinement. With the rise of industrialization and the stress of modern urban life, affluent Americans sought reprieve in places like:

- Saratoga Springs, NY – Known for its over 20 mineral springs, this resort town became a magnet for East Coast elites and celebrities. Bathhouses, casinos, and grand hotels turned health into spectacle.

- Hot Springs, AR – Marketed as “America’s Spa,” it attracted presidents, gangsters, and athletes alike. The federal government even designated it as the first U.S. National Reservation in 1832 — a precursor to the National Park system.

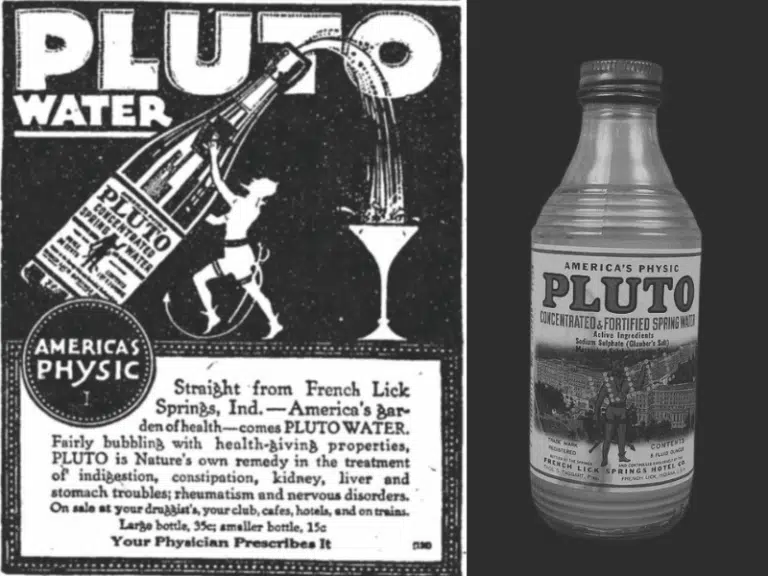

- French Lick and West Baden Springs, IN – These resorts featured “Pluto Water” and boasted massive atriums and domed architecture rivaling European palaces.

- The Greenbrier, WV – Known as the “Old White,” this spa played host to America’s elite, offering sulphur spring treatments with all the refinement of an international social club.

While European spa culture focused on therapeutic regimens and communal rituals, American grand spas of this era became symbolic playgrounds for the wealthy. Here, “taking the waters” was less about curing illness and more about reaffirming social status through leisure*.

Still, it’s worth noting the contrast: mineral springs were heavily marketed as cures for countless ailments, from digestive issues to melancholy. Hydrotherapy wasn’t just a luxury — it was often sold as a medical necessity. For many, the spa experience straddled two realities: part genuine pursuit of health, part performance of it.

A stage for women’s autonomy

Interestingly, these grand spas also provided rare spaces for women to travel, rest, and connect independently. While still governed by societal expectations, spa resorts offered elite women a chance to focus on self-care, engage in mild physical activity, and even make social or philanthropic connections away from male-dominated spheres.

Some historians argue that these resorts laid early groundwork for modern concepts of female wellness empowerment — albeit within a framework steeped in privilege. In this light, reclaiming spa rituals today also means reclaiming autonomy — creating space for intention, restoration, and personal authorship, beyond consumerism.

Nature, bottled and branded

The mineral springs at these spas were touted as miracle cures for everything from gout to melancholy. The belief in hydrotherapy and balneotherapy (therapeutic bathing) led to highly ritualized experiences: cold plunges, steam cabinets, electric baths — even early versions of colonics and saunas.

But as demand grew, many resorts began bottling and branding their spring waters — commodifying nature itself. “Pluto Water,” from French Lick, for instance, became so popular it was sold nationwide as a laxative, using slogans like “When Nature Won’t, Pluto Will.”

Today, a new wellness ethic asks us to rethink this dynamic. What if we didn’t consume nature, but collaborated with it? Nature as a co-participant — not just as a product, but as a therapeutic ally. In modern spa design, this shift shows up through biophilic design — integrating natural light, raw textures, open-air elements, and even living systems that restore not just the individual, but the planet itself.

The birth of wellness tourism

These grand spas weren’t easily accessible by foot or horse. Their popularity surged with the advent of railroads, which turned them into early wellness tourism hubs. Package deals included stays, treatments, entertainment, and full meal plans. Much like today’s all-inclusive resorts or destination retreats, these spaces allowed guests to escape, recover, and re-enter society “renewed.”

It was wellness as both experience and performance — something we still see in Instagrammable retreat culture and status-oriented health trends today. And like their historic counterparts, today’s resorts must now confront deeper questions: Who gets access? Who gets left out?A complicated legacy

As beautiful and culturally rich as these resorts were, they were also sites of exclusivity. These spaces were largely inaccessible to Black Americans, immigrants, and lower-income citizens. Racial segregation and economic barriers kept them out. Their legacy includes a selective wellness movement — a shadow that the modern spa industry continues to reckon with.

Today’s conversations around inclusive design, community care, and decolonizing wellness are, in some ways, attempts to untangle this past. This includes asking:

- Whose healing traditions are honored versus appropriated?

- Who can afford to participate in wellness today?

- How do we acknowledge the cultures and communities long excluded from spa culture?

Decolonizing wellness is about more than representation. It’s about reshaping systems to make space for diverse bodies, beliefs, and needs. Inclusive design means more than ADA compliance. It’s a design mindset that centers empathy, adaptability, and dignity.

What can we learn?

The Gilded Age spas were ambitious, symbolic, and highly experiential. These are values we see now re-emerging in modern wellness design. But their history also invites us reflection on an important question. Who is wellness really for? And how we can create spaces that heal without excluding?

As the wellness industry evolves, we can draw from this history to:

Reclaim ritual and intention in spa experiences — moving beyond trends toward deeper meaning.

Re-center nature as a co-participant, not a product — creating spaces where the environment heals with us, not for us.

Design inclusive spaces that honor the diversity of today’s seekers — through cultural literacy, sensory access, and affordability.

Closing thought

In their time, America’s grand spas were temples of transformation. Today, they’re reminders — of how far we’ve come, and how far we still have to go in making wellness a truly democratic experience.

As we stand at the crossroads of innovation and reflection, perhaps the most radical act is to look back — not to romanticize the past, but to learn from it.

Want to take this exploration further? Check out the Google Map of iconic U.S. spa destinations I created. It’s a living, curated layer that connects these historic legacies to real-world places you can still visit today. Each destination offers a glimpse into America’s evolving relationship with health, beauty, and escape. These are not just relics — they are living chapters in a continuing story of wellness.

Looking for today’s sanctuaries of self-care and escapism? Explore the evolving landscape of wellness providers at Spadweller.com — a directory designed to help you find your modern ritual.

*Sources and Citations:

1. Carl J. Schneider, Taking the Waters: Spirit, Art, and Leisure in the Gilded AgeSchneider illustrates how spas like Saratoga Springs served more as social arenas than medical retreats. He writes, “To take the waters was as much a ritual of conspicuous consumption as it was a pursuit of wellness.”

2. Gary S. Cross, A Social History of Leisure Since 1600

Cross details how 19th-century leisure spaces like spas reflected elite values. He notes, “By the late 19th century, spas had shifted from healing centers to elite social spaces, where appearances mattered as much as ailments.”

3. Jane E. Dabel, “The Healthful Resort: Health, Nature, and the Spa in Nineteenth-Century America”

Published in The Journal of Historical Sociology, this article explores how spas reinforced class and racial divides. It highlights how many resort spas functioned as exclusive spaces for the upper classes.

4. Historical newspaper ads and social columns (e.g., New York Times archives, 1870s–1900s)

Spa promotions from this era often emphasized leisure activities, such as balls and horse racing, more than medical benefits — reinforcing their role in social performance.

5. Mark Twain, The Gilded Age (1873)

Though fictional, Twain’s satirical take on upper-class habits reflects the common understanding of spas as status-signaling destinations: “They came not to be cured, but to be seen in their convalescence.”